Background

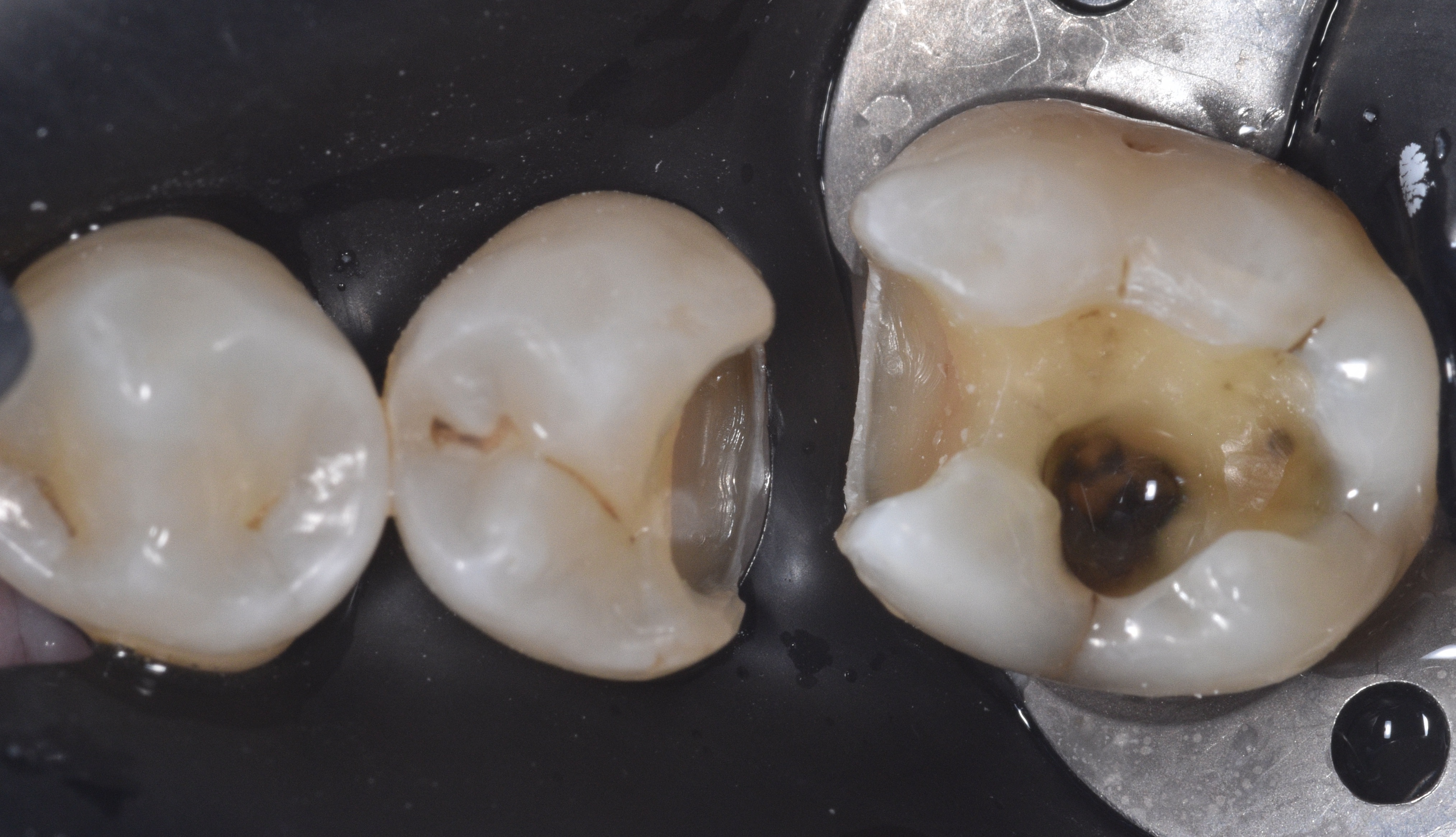

A 51-year-old man in good health came to my office with large carious lesions between teeth #29 (DO) and #30 (MO). As seen in the pre-op photo (Figure 1), this case was challenging because both teeth were rotated: tooth #29 was rotated toward the lingual and #30 toward the buccal, creating wide embrasures and a relatively small contact area.

|

| Figure 1. Patient presented with large carious lesions between teeth #29 (DO) and #30 (MO). |

Pre-operative Case Analysis

When choosing a matrix system for this situation—given the positions of the teeth and size of the preparations—it’s important to consider:

1. How far apart are the adjacent preparations?

2. How deep are the proximal boxes?

3. Is it feasible to restore both teeth at once?

As shown in Figure 3, there is about a 3mm space between the preparations, indicating that firm stainless steel sectional matrix bands are necessary. These stiffer bands are less likely to deform when wedged near the gingival margin, which is crucial for achieving an ideal emergence profile.

The depth of the boxes also impacts the appropriate ring and wedge. The “Romero DME technique” recommends theQuad ring and wedge for single band DME cases. While some clinicians suggest using a special DME band followed by a sectional band—or even a “band within a band” strategy—they often overlook that these methods can leave a difficult-to polish transition line between composite layers, potentially harboring bacteria.

Restoring both teeth together only works if the bands and rings fit precisely. In Figure 8, the Quad ring couldn’t fully adapt the band to the lingual side of #29 due to rotation. Consequently, we kept both bands in place, restored #30 first, then removed its band and ring, repositioned the ring for a proper fit on #29 (Figure 10), and finished the second restoration.

Clinical Procedures

After ensuring profound anesthesia with two carpules of OraBloc Articaine 4% containing epinephrine 1:100,000 administered via an inferior alveolar nerve block (IANB), rubber dam isolation was established to maintain a clean and dry working field. Access to the carious lesions was achieved using a #2 round diamond bur. As observed in Figure 2, the enamel exhibited areas of demineralization, and there was dark, infected dentin extending beyond the dentinoenamel junction (DEJ). Caries detection dye was employed to guide the excavation until all carious tissue was removed and a sound peripheral seal zone was obtained.

|

| Figure 2. The enamel exhibited areas of demineralization, and infected dentin extending beyond the dentin enamel junction (DEJ). |

Following caries removal, the walls of the cavity preparations were beveled using a fine diamond mosquito bur, as shown in Figure 3. The prepared surfaces were then air abraded with 23-micron aluminum oxide particles combined with distilled water, using the AquaCare system, to further clean and prepare the tooth structure for restoration.

|

|

|

| Figure 3. Walls of cavity preparations were beveled using a fine diamond mosquito bur. | Figures 4-5. Quad wedge and ring system used for this case. | |

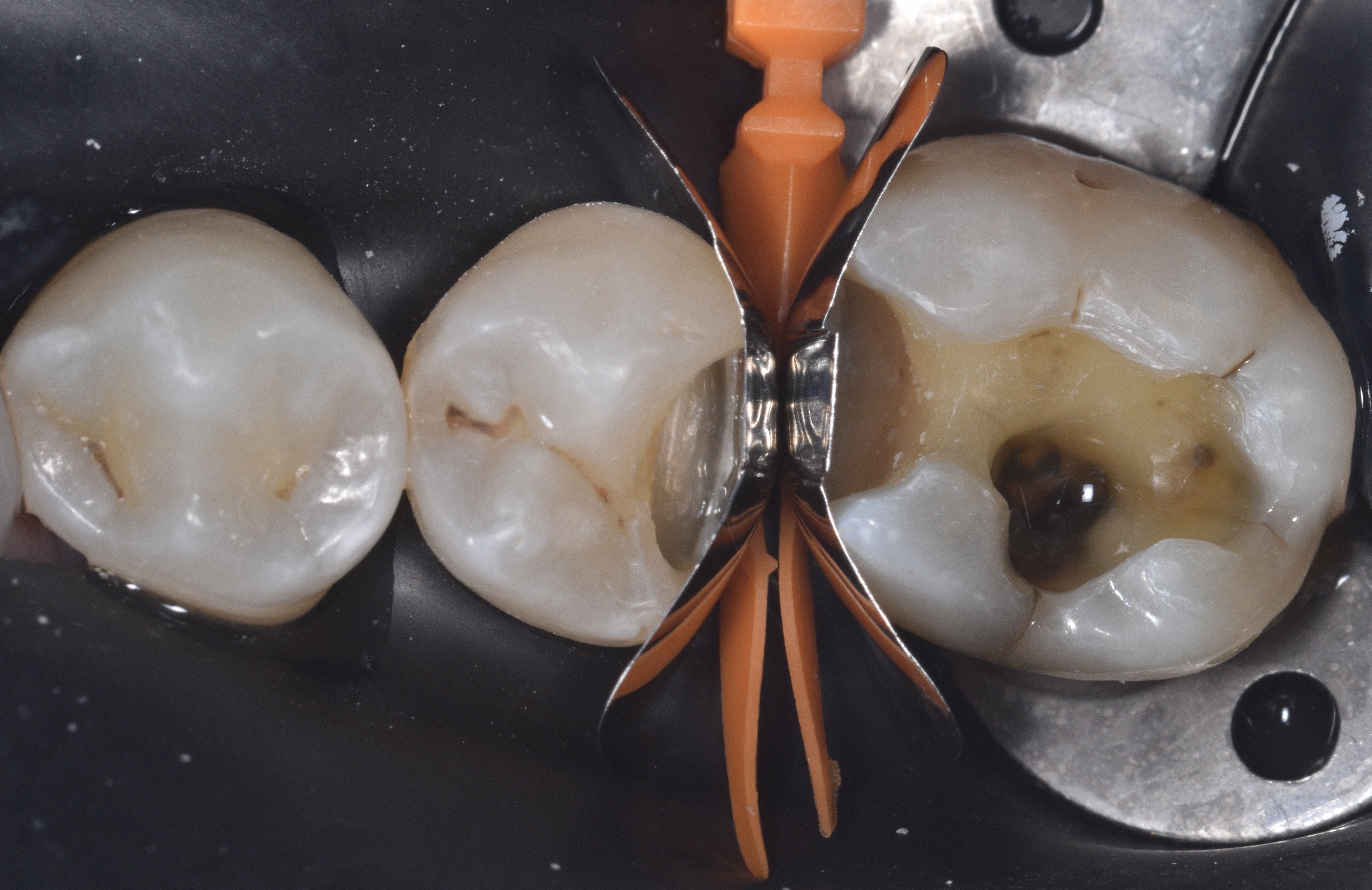

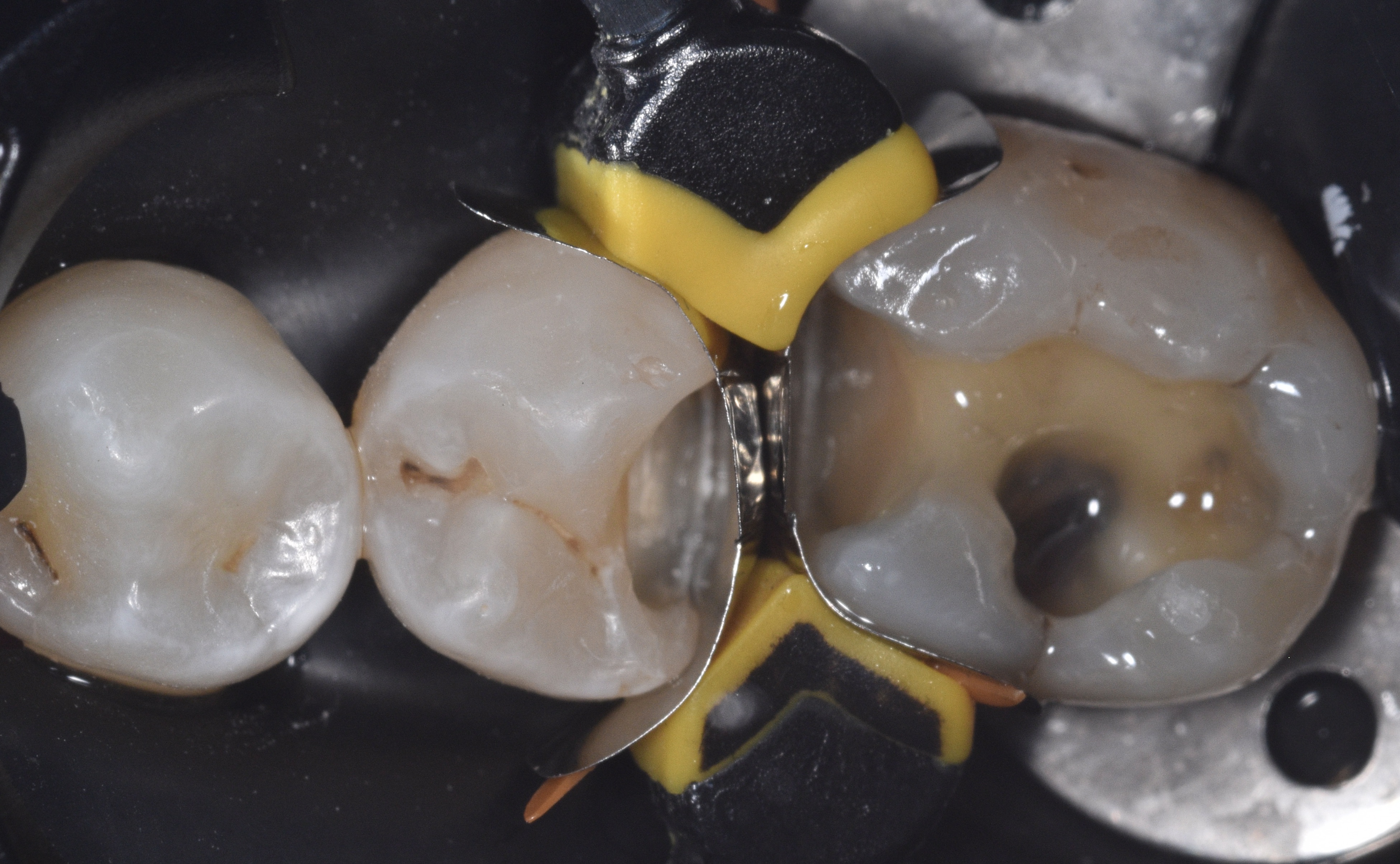

Figures 4 and 5 display the selected QUAD wedge and ring system for this case. The ring features an arrow-shaped driver tip (Figure 6) that fits into the split portion of the wedge, pressing the matrix bands mesially and distally to improve adaptation to the tooth contours. In Figure 7, the medium QUAD wedge securely holds the firm stainless-steel matrix bands in place, while Figure 8 illustrates the placement of the ring and the action of the driver tip in splitting the wedge on the lingual surface, enhancing the contouring of the bands.

|

|

|

| Figure 6. The Quad ring driver tip designed to fit into the split portion of the wedge. | Figure 7. Medium Quad wedge securely holding the firm stainless-steel matrix bands in place. | Figure 8. Quad system placement shown enhancing the contour of the bands. |

However, it is important to note that the band could not be fully adapted to the distal-lingual margin of the proximal box on tooth #29. This limitation made simultaneous restoration of both teeth unsuitable for this clinical scenario. Consequently, the decision was made to restore one tooth at a time while keeping both sectional matrices in place to prevent interference between restorations.

The next steps involved selectively etching the enamel and applying Optibond extra universal (Kerr) primer and adhesive. The deep margin elevation (DME) procedure was performed, followed by incremental buildup of the proximal wall (Figure 9) and individual cusps until the tooth was fully restored (Figure 10) using a single shade of A2 D Harmonize (Kerr) composite. Once the restoration on tooth #30 was completed, the ring and sectional matrix band were removed, and the ring was reseated to ensure optimal adaptation of the band on tooth #29 (Figure 11), resulting in a tight contact between the band and the adjacent interproximal contact (IP).

|

|

|

| Figure 9. The deep margin elevation (DME) procedure was performed, followed by incremental buildup of the proximal wall. | Figure 10. Tooth #30 fully restored using a single shade of A2 D Harmonize (Kerr) composite. | Figure 11. Quad ring and band removed and reseated to ensure optimal adaptation of the band, and tight contact on tooth #29. |

Figure 12 demonstrates the completion of the DME with a single horizontal layer of Harmonize composite (Kerr), while Figure 13 shows the subsequent composite layer used to build the proximal wall. The completed restoration is depicted in Figure 14, and Figure 15 displays both teeth after finishing and polishing, highlighting the natural contours of the embrasures and the anatomical IP contact achieved.

Finally, the bitewing (BW) x-ray (Figure 16) confirms the ideal emergence profile at both deep margins, primarily due to the flexibility of the split wedge, as well as the proper anatomical interproximal contours resulting from the selected matrix bands.

Considerations

One of the primary reasons clinicians often opt for crowns instead of direct composite restorations in cases involving deep and wide Class II lesions is the high degree of technique sensitivity associated with direct composite procedures. The complexity of these restorations can present challenges that may impact the long-term success of the restoration. Simplifying the restorative procedure—by minimizing the amount of equipment required and reducing the number of clinical steps—not only enhances the clinician’s motivation but also contributes to a higher likelihood of a successful outcome.

|

|

| Figure 12. DME complete with a single horizontal layer of Harmonize composite (Kerr). | Figure 13. Subsequent composite layer used to build the proximal wall. |

|

|

| Figure 14. Completed restoration shown. | Figure 15. Both teeth after finishing and polishing. |

|

| Figure 16. Bitewing x-ray confirms the ideal emergence profile at both deep margins. |